One of the more interesting learnings I’ve learned at Kapost is what makes SaaS business models work. Related to that I often get the question asked to me, “How is Kapost doing? Is it profitable yet?” implying that if it isn’t, things are bad and if it is, then things are good. This post is an attempt to address that question.

When talking about a company’s performance, I’ve noticed that you have to talk about both its growth and profitability, and discussing just one in the absence of the other is dumb.

I recently did a post comparing Salesforce and Linkedin. You’ll notice in there that neither company is profitable yet both are worth over $30 billion dollars. LinkedIn makes a $1 billion a year in revenue, whereas Salesforce does $1 billion a quarter ($4 billion a year). Why are they worth the same? Because LinkedIn is growing at 60% a year whereas Salesforce is growing at 30%.

To investors, companies are worth what their cash flow is going to be in the future – not what it is now. That’s all they care about. If they think the cash flow will be huge, the company will command a huge valuation.

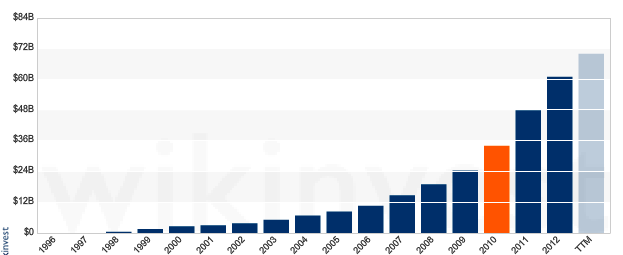

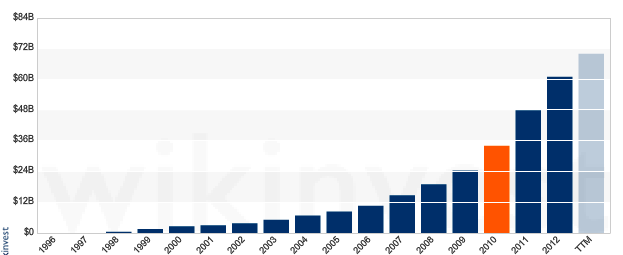

Let’s take Amazon.com as an example. They have had no profits for years, yet it’s currently worth $166 billion. One analyst even jokes about it, writing:

With every Amazon quarterly earnings call, my Twitter feed lights up with jokes about how Amazon continues to grow its revenue and make no profits and how trusting investors continue to rewards the company for it. The apotheosis of that line of thoughts is a quote from Slate’s Matthew Yglesias earlier this year: “Amazon, as best I can tell, is a charitable organization being run by elements of the investment community for the benefit of consumers.”

The point here is that you need to understand why any company is not profitable. In the case of Amazon, it is making huge investments in warehouses to grow its retailing business and huge investments in data centers to grow its AWS business. It could stop making those investments and start generating profits. But doing so will sacrifice growth in the market they current work in. Amazon’s doing $70 billion in revenue this year and did $34 billion in 2010. Here’s Amazon’s revenue since 1996:

That’s doubling in 3 years. That’s pretty amazing. I’m sure it’d be worse if they were focusing on profitability.

What does this mean for Kapost? Kapost has established itself as the market leader in content marketing software and hit profitability early in 2013. However, we desired to grow and grow quickly. Thus, we raised a round of funding and are using the those funds to accelerate our growth.

Why can’t we grow organically with our profits?

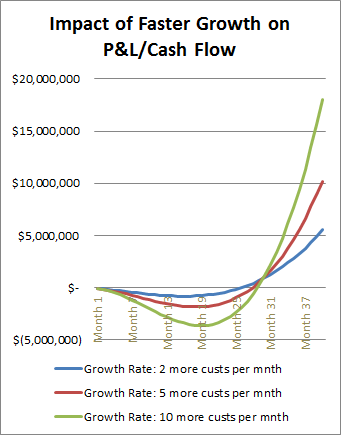

The way SaaS businesses work is that they face significant losses in the early years because they have to invest upfront to acquire customers, but they recover the profits from that investment over a long period of time (the life of the customer). What’s somewhat strange for people to understand about SaaS businesses is that the faster the business decides to grow, the worse the initial losses become.

For example, imagine a world we you spend $6,000 to acquire a customer, and then charge them $500 per month. For one customer, you’ll get the money back after a year, but you need $6k up front first to get them. And, if you want to grow faster and get even more customers, you have to spend even more money. The graph below shows that the more you spend, the better the rate of growth is.

This is why Kapost did another round of funding. Going forward, as long as we’re accelerating the rate of revenue growth, we’ll always be needing more money and more money that we’ll need to fund that growth. That is, unless we don’t want our rate of growth to increase.

Now, of couse, profits are critical to the health of a business. The key is to be able to be profitable if we want to be and to be profitable at some point in the future, at least hypothetically. So, when you hear that a company is losing money, don’t read that as a necessarily bad thing. It could be a very good thing. It all depends on why.

———

Notes: Here are some good posts on this topic that helped me out:

- David Skok is awesome. I stole his graph and a lot of his thoughts.

- Wikivest

- From Eugene Wei’s blog

- From Fred Wilson’s blog